In many organizations, people still speak of “human resources”—a term that implies employees are deployable assets to be optimized like machines. But an organization is not a well-oiled machine. It is a living system where people collaborate, communicate, and create. HR professionals and managers who truly want to make a difference look beyond structures and job descriptions, starting instead from the understanding that humans are relational and social beings.

Organizations operate on the basis of collaboration—and this collaboration can, in fact, be steered. Henry Mintzberg, a leading organizational theorist, identified six coordination mechanisms that describe how people align their efforts to achieve shared goals. Each mechanism offers a different way of synchronizing work, sometimes explicitly through agreements and structures, and sometimes implicitly through culture and trust. The key is that successful organizations apply these mechanisms consciously and in ways that fit their specific context. There is no “one best way”—it’s about finding the right mix, tailored to the culture, complexity, and maturity of the team.

Each mechanism offers its own perspective on how teams function, and together they form a rich palette of possibilities. In this blog, we’ll explore them all.

1. Mutual Adjustment: Trust and Flexibility

The most human form of coordination is mutual adjustment. Colleagues communicate directly, make informal agreements about who does what, and step in to support each other where needed.

Example: In a small consultancy team with a high degree of autonomy, colleagues meet on Monday morning to decide who will follow up with which client, distributing tasks based on availability and expertise. There are no rigid rules—just open dialogue and mutual trust.

This way of working is particularly effective in small, agile teams and relies on a strong culture of trust, shared ownership, and well-developed communication skills.

2. Direct Supervision: Guidance and Safety

Sometimes direct leadership is necessary. In this approach, a manager takes the lead—providing direction, making decisions, and assigning tasks.

Example: During a crisis in a production environment, the shift supervisor steps in and immediately (re)distributes tasks to get the halted production line operational again.

Direct supervision creates clarity and provides a sense of safety in acute or complex situations. It offers temporary stability when swift action is crucial—but it only works effectively when paired with respectful communication and clear expectations.

3. Standardization of Work Processes: Structure and Efficiency

When tasks or processes are repeated frequently, it can be useful to introduce fixed procedures or work instructions.

Example: In a customer service team, it is agreed that every incoming complaint must be registered within 24 hours according to a fixed procedure.

This approach creates clarity, reduces errors, and speeds up the onboarding of new colleagues. However, standardization should be supportive, not restrictive—leaving space for judgment and human interaction.

4. Standardization of Outputs: Autonomy with a Goal

In this form of coordination, no specific tasks or methods are prescribed, but clear, measurable objectives are agreed upon. This leaves room for autonomy, allowing employees to decide their own approach as long as the desired result is achieved.

Example: A sales department is tasked with acquiring five new clients each month, without any prescription for how to achieve it. This works well for independent, experienced professionals who value ownership and are motivated by accountability for results.

5. Standardization of Skills: Investing in People

Some tasks require specific knowledge or expertise. By investing in targeted training and development, you not only improve work quality but also strengthen mutual understanding and alignment within teams.

Example: In a wellbeing organization, all employees participate in annual training on nonviolent communication, enabling them to engage in better dialogue with both clients and colleagues. Standardizing skills boosts performance while reinforcing professional identity and employee confidence.

6. Standardization of Norms: Culture as the Coordinator

Finally, there are the shared values, beliefs, and behavioral expectations that implicitly shape how people act within an organization.

Example: In a sustainability-focused company, it’s “normal” to provide plant-based snacks during meetings or to expect eco-conscious printing habits—not because it’s enforced, but because it feels natural.

When norms are widely embraced, they create strong social cohesion. Employees act from a shared compass, which fosters direction, trust, and connection—even without formal rules.

The Art of Combination

In reality, none of these mechanisms exists in its pure form. Most organizations operate with a mix of coordination styles—and it’s precisely this combination that makes them dynamic and effective. A start-up that thrives on mutual adjustment may still benefit from a few well-defined processes. A large, rule-driven organization can flourish when there is also room for dialogue and initiative.

The question isn’t which mechanism is “best,” but how to find the right balance that fits your mission, team size, and culture. Above all, it’s about recognizing that people are not cogs in a machine—they are relational beings who want to contribute, learn, and create meaning together at work.

When organizations use their coordination mechanisms with an eye for both efficiency and humanity, something remarkable happens: they stop being a collection of human resources and become a vibrant community of people.

Looking for support in building a positive, motivating, and psychologically safe company culture?

For employees: “The Power of Optimal Collaboration”

Healthy, engaged employees can only deliver outstanding results in a team where they feel good and in a company that shares their values. In this session, employees discover the impact they themselves have on collaboration within and beyond their team, and how they can use communication to strengthen and optimize professional relationships.

For leaders: “Creating a Speak-Up Culture”

A workshop packed with tips and techniques for fostering healthy, assertive communication and a speak-up culture. After all, communication is a shared responsibility—everyone can help build a company culture that encourages people to speak their minds. On the agenda: setting boundaries, saying no constructively, asking for help, handling conflict in a healthy way, and more.

For leaders: “Giving and Receiving Trust—Also in Remote Work”

Many managers fall into the trap of micromanagement. This can not only create stress within the team, but by taking work out of their employees’ hands, managers themselves may end up heading toward toxic stress—or even burnout. In this interactive session, participants learn how to lead in a healthy way by building on trust, and we walk through the 7 building blocks of creating psychological safety.

Do you want to foster a positive and people-centered company culture? Be sure to check out our offer!

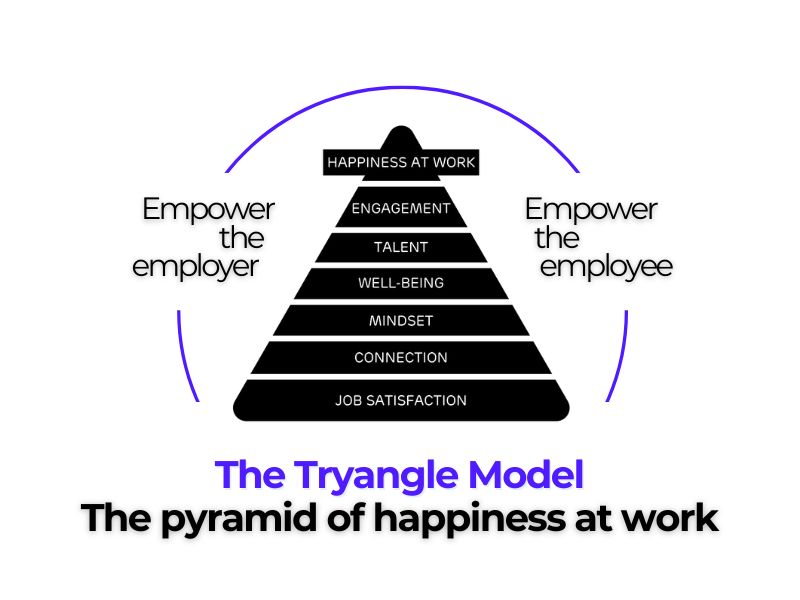

Based on our own pyramid model, we raise awareness in organizations about the components, opportunities, and ROI of workplace wellbeing and happiness.

We provide solutions for organizations, leaders, and individual employees, driven by our belief in the shared responsibility between employer and employee. Every intervention is tailor-made to fit the company culture and aligned with the organization’s priorities and needs.

Curious to see how we can help you?

Discover our services and topics or download our folder

About the author of this article

Kim Hilgert is a Corporate Well-Being Expert and co-founder of Tryangle. As a wellbeing trainer and consultant, she helps companies develop and implement a sustainable wellbeing strategy or workplace happiness policy. Her mission? Empowering people to (re)discover their strengths—boosting engagement, increasing productivity, and reducing absenteeism.

Kim is an enthusiastic trainer, consultant, webinar host, and coach. She loves to encourage interactive participation, learning by doing, and critical thinking. Her preferred approach combines practical exercises with science-based insights and techniques that can be applied immediately.